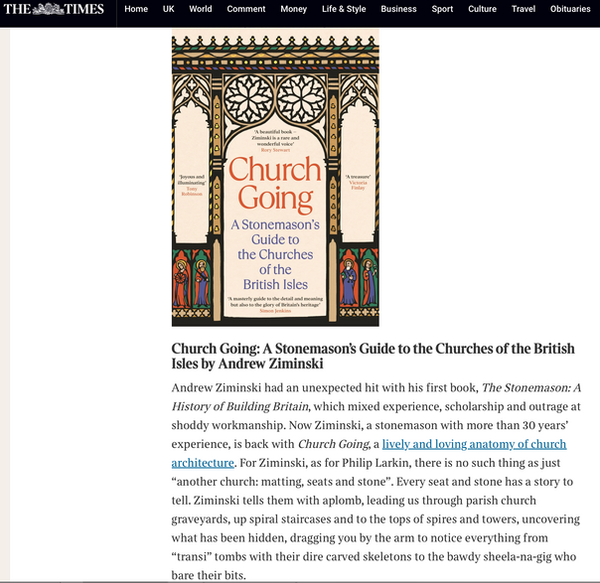

Church Going

by Andrew Ziminski

As a stonemason with 30 years' experience in mending historic buildings, Andrew Ziminski is a guide who notices useful things. He has also visited more than half of Britain's 10,000 churches of medieval origin.

His chosen task in this successor to The Stonemason (2020) is to tell the story of medieval churches by exploring their physical parts, from squints to weathervanes. The weathervanes he often finds are riddled with bullet holes from amateur marksmen. Just as handy are the author's telling questions. So, in a little section on font covers, he notes that St Edmund of Abingdon, Archbishop of Canterbury, directed in 1236 that all fonts should have a lid with a lock to prevent the holy water from being used for black magic. Ziminski questions this directive since the same holy water was freely available from the stoup by the door. In the charmingly titled Fonts and Font Covers (1908), the antiquarian Francis Bond quoted the injunction, giving the reason as propter sortilegia. Sortilege is principally divination of the future, so perhaps font abusers looked into the water as into a magic mirror. Who knows? But it is our good fortune that some font

covers are glorious, soaring Gothic structures, as at Salle, Norfolk, pictured in this book.

At Steeple Ashton, Wiltshire, he finds that four flying buttresses have been removed. Why? In the churchyard are remnants of the previous heavy slate roof. The steeple that gave the place its name crashed through the nave roof in 1670, and a wooden vault replaced solid stone. If the buttresses had not then been removed, they would have pushed the lighter nave walls inwards till they collapsed.

Ziminski's pace is brisk. No sooner is he up the tower of St Paul's, Jarrow, observing that the marshes where St Bede could have got writing quills from ducks are now concreted over and covered by thousands of new Nissan cars, than he is briskly off and up the tower of St Peter's, Monkwearmouth, with a bin bag to collect the dead pigeons, happily inspecting Saxon lathe-turned stone balusters.

He has a deep delight in timber, too, beginning with St Andrew at Greensted-juxta-Ongar (a little further from the London Underground since the extension from Epping was closed in 1994), built before the Conquest from 51 split tree trunks in a palisade, the oldest wooden church in the world. In the dark winter interior, he imagines the body of St Edmund, King and Martyr, lying there for the night in 1013 on its way from London back to Bury St Edmunds.

The fretted and painted wooden chancel screen (inspired by Edingthorpe) on the dust jacket was done with paper cutouts by his wife Clare Venables, who also drew the atmospheric illustrations, with their daughter, Violet.

"Further Reading" is temptingly chosen, adding to Eamon Duffy and John Betjeman, indefatigable researchers of today, such as C.B. Newham on Country Church Monuments and Justin Lovill on Old Parish Life.

The title is from Larkin's poem of course, and the book's final section features the twilit Norman crypt at Lastingham, North Yorkshire (founded in the 65os, like Greensted, by the mission-minded St Cedd).

Here Ziminski half answers the poet's own telling questions about the future of old churches, perhaps reduced to ruin and brambles. "The Church of England may seem to be on its knees," he concludes, "but as long as prayer continues in such places, I suspect that churches like this one at Lastingham will continue to be used for another 1,000 years, for whatever version of religious faith comes along next."